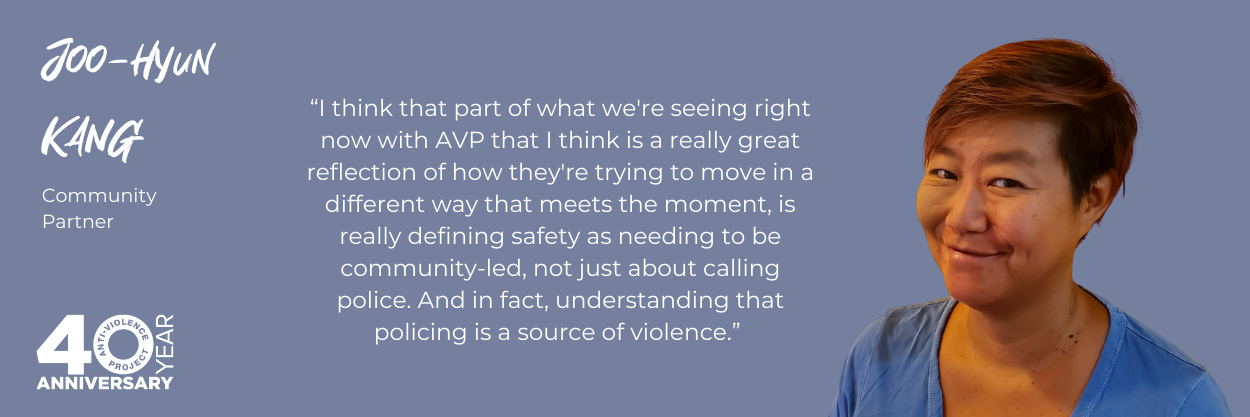

Joo-Hyun Kang is a longtime organizer in LGBTQ and social justice communities in New York City and a mentor to many. She was a program director at Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice and the first staff member and director of the Audre Lorde Project, an organizing center for LGBTST (lesbian, gay, bisexual, Two Spirit, and transgender) and gender-nonconforming communities of color.

Until recently Joo-Hyun Kang was the director of Communities United for Police Reform (CPR), a campaign to end abusive and discriminatory policing in New York, which comprises over sixty organizational members from all five boroughs including AVP and over 140 other organizational members of campaigns run by CPR. While at CPR, Joo-Hyun was one of the key organizers responsible for the dramatic reduction of the NYPD’s “Stop and Frisk” policy which disproportionately harmed Black and brown and LGBTQ New Yorkers. While Joo-Hyun’s early interactions with AVP prior to working with CPR were difficult, AVP became a founding member of CPR and the two organizations worked together over the past decade on a variety of issues and campaigns.

“I think that part of what we’re seeing right now with AVP that I think is a really great reflection of how they’re trying to move in a different way that meets the moment is really defining safety as needing to be community-led, not just about calling police. And in fact, understanding that policing is a source of violence.”

Below we discuss broad coalition organizing, police brutality, leadership, and living out your values.

How did you first come in contact with AVP?

I heard about AVP first in the early ’90s, just as a resource for the queer community, but I started to do some work with AVP folks when I was at the Audre Lorde Project a hundred years ago when the Audre Lorde Project was first founded.

When I was at the Audre Lorde Project, we did some work with AVP because we were part of a grassroots, anti-police violence coalition at the time called Coalition Against Police Brutality that used to run an annual racial justice day march and other actions.”

We worked with [AVP] initially on a police violence case involving an attack on a trans woman and her family in the projects in the Bronx. AVP was the first group we reached out to, to do some direct work with us on it, but we actually ended up not working with them on it.

Some of that was not a great experience. Part of the conflict was that [AVP] saw it primarily as a kind of a trans, queer case only. And this was a case that was very much about policing in public housing. So it was about class and it was also about race. And of course, it was also transphobic violence, but it wasn’t something that you could just separate out in those ways. So we had a principal disagreement there, but also a strategic disagreement. We ended up working with a group at that point called National Congress For Puerto Rican Rights, which is now known as the Justice Committee.

And I feel like, for me, that’s a lot of what has changed about AVP. AVP is much more clear, it seems, at least from the outside, about the need to centralize the experiences of those who are most likely to experience violence in New York City. And that includes not only trans and gender-nonconforming folks, it includes low-income people, immigrants, and certainly Black and other people of color. And that wasn’t necessarily as much in AVP’s DNA I would say in the ’90s in terms of how that gets really integrated through its work.

The past decade or so I worked with AVP because they were part of a coalition I ran called Communities United for Police Reform (CPR). I feel like that team in many ways set up AVP to be seen differently than it was, especially by some of the more grassroots trans and queer of color groups in New York City as more of a partner, less of a grasstops-only organization, more willing to get their hands dirty and be willing to really stand up for political principles.

Can you describe any of those things that AVP and CPR worked on together in that coalition?

There’s a number of legislative fights that AVP folks were part of. That included city-level fights to pass local legislation to reduce police violence. They were involved in helping to Repeal 50-a, which was a statewide police secrecy law as part of CPR. And then they also contributed significantly in terms of some of the non-legislative work, like Know Your Rights trainings, some of their folks were also media spokespeople and they, along with Audre Lorde Project and some of the other queer organizations that were involved in various CPR work, I think, played an important part of really articulating what the trans and queer piece of police violence was, but also organized more broadly within their communities on that.

I think that part of what we’re seeing right now with AVP that I think is a really great reflection of how they’re trying to move in a different way that meets the moment is really defining safety as needing to be community-led, not just about calling police. And in fact, understanding that policing is a source of violence.

And also even the work that folks like Reem [Ramadan, Manager of Organizing and Advocacy] and other folks [at AVP] are doing right now to really help folks have an understanding of what the history of Pride is and that it was actually a rebellion against police violence and state repression. And that means that it’s incompatible with celebrating cops at Pride. Some of the positions they’ve taken, I think, are different than they would have in some of the earlier years, which I think is really helpful now because we’ve seen so much depoliticization of trans and poor communities broadly in the past number of years for various reasons. I think AVP has actually only gotten sharper and more principled.

What are some of those values that you feel AVP is living out?

They are consistent and clear about centering racial justice. They’ve been more and more consistent about centering the leadership and promoting leadership of transgender and gender nonconforming people and that there’s much more of an openness, and I don’t mean diversity of staff or diversity of board stuff that only goes so far, but more of a clear understanding that to deal with violence against trans and queer and gender nonconforming folks, we need to actually think about violence broadly and the various ways in which many people are not safe or don’t feel safe. That doesn’t mean watering down their mission. It means actually being clear about where the contradictions are, where the opportunities to work with ally communities are, and just sharpening your strategy.

Can you walk me through what you saw working internally with AVP on some of those cases?

In June 2020, when there were mass protests across the country, the biggest protests we’ve seen across the country, pretty much on any issue after the killing of George Floyd and in defense of Black lives, you probably remember that there was an occupation at City Hall calling for a defunding of the NYPD. And there was one day during that where folks who had been camping outside of City Hall got attacked by the cops that night. So in the morning, some of the organizers called me and said, look, we’re going to need some help on the ground today, especially with media. I put out a call to some of our folks who have comm[unications] staff, [because] many of the groups within CPR didn’t actually have dedicated comm[unications] staff. And [former AVP Director of Communications, ] Eliel [Cruz] worked it out to be there, and also help prep some folks to be able to be spokespeople. He did some media interviews himself, but he also just really tried to be accountable to the overall coalition.

I feel like that actually shows a level of organizational maturity, I just don’t think should be taken for granted. There are a lot of organizations, especially mid-size and larger organizations, where there might be some individual staff who are great, but that’s not reflective of the overall organization. I think that what AVP has tried to do over the past decade or so is really ensure that the organization as a whole is really pushing together in a unified way so that there is an internal coordination of strategy as well as philosophy that shows up in their public work.

Why do you think anti-violence organizations like AVP or CPR are necessary?

We’re in this period right now in this country where there is a huge and rapid acceleration of a very authoritarian, right-wing agenda that’s been in the works for decades. The last time we saw something so rapid in terms of acceleration of a right-wing agenda was probably right after 9/11, in New York City. And that was more [from] the federal government and the Patriot Act, and then more locally in New York City, the deep militarization and expanded power of the NYPD. But in this period, post-Trump, having gone through the Trump era, which I guess people can debate whether or not it’s over, but then also the recent Supreme Court ruling on Roe [v. Wade], and the legislative attacks across the country in terms of trans communities, gender non-conforming children, and their families.

And what we’re seeing is the continued rise and emboldening white supremacy, normalizing white supremacy.

I think that organizations like AVP that have a strong local presence in New York City, that’s rooted in community, that’s trying to expand their base of community, and engagement of community are critical. We need more organizations that have a national outlook and that are grounded in actual relationships with people in other states with work in New York. I think that the evolution of AVP’s thinking around what community safety means – that it’s not synonymous with calling the cops – is an important shift. And in fact, that calling police shouldn’t be anybody’s first or only choice. There should be other options available to people. It’s part of what we need to fight back against authoritarianism. It’s… about how we use vehicles like AVP to not only engage community members but engage them in a project to actually have more people be free in New York City. Be free, be able to live and thrive, be able to be their full selves. It’s one of the best parts of the trans and queer movement, I think is an understanding of what it means to find joy and celebration in the midst of ongoing attacks and violence. And that gift of joy and celebration is something that helps to invite and recruit more people into not only a particular project that AVP might be doing but really into a project of strengthening democracy locally.

This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.