This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.

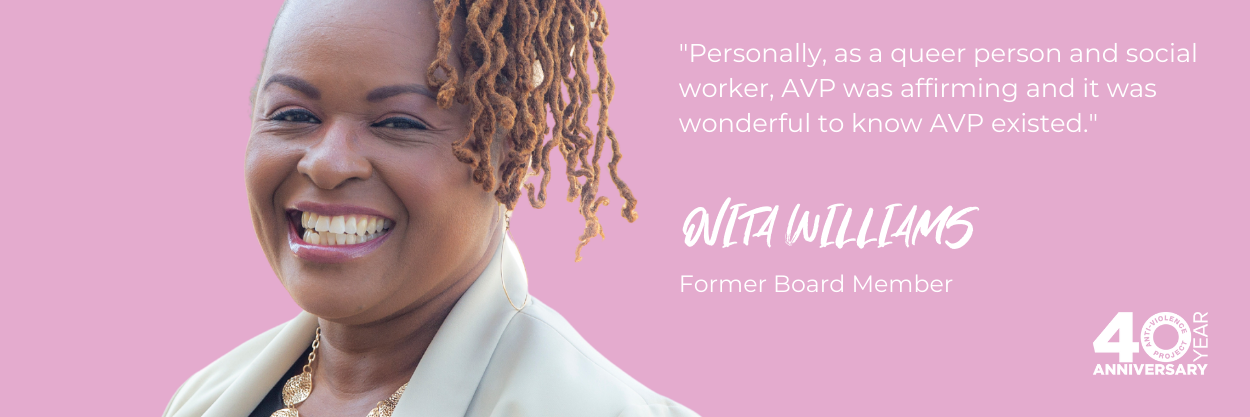

Ovita Williams is the Executive Director of the Action Lab for Social Justice at Columbia University and has been working with the next generation of social workers for 17 years. As an Afro-Caribbean woman whose parents immigrated to the US in the 1960s, being surrounded by people who want to shake things up and change systems is a part of Ovita’s everyday inspiration.

The first time Ovita came into contact with AVP, she was blown away.

“It was also just so imperative to know that this organization existed,” she said. As a queer woman, she felt moved to start attending more events and committees led by AVP until she finally joined the board.

Can you describe your experience witnessing AVP’s work?

I was working at the Kings County DA’s Office in the Counseling Services Unit as a social worker supporting intimate partner violence survivors. We referred survivors to AVP for counseling and other resources. The provision of services for the LGBTQ community inspired me to get involved. Many organizations were not able to provide services that were comprehensive and LGBTQ+ friendly. Personally, as a queer person and social worker, AVP was affirming and it was wonderful to know AVP existed.

What have been some of the biggest obstacles in your work?

I remember police officers and lawyers, some lawyers would say, How could there be [abuse] in a lesbian or gay relationship? I don’t understand.” They would actually say, “Well, it was two women when we got to the house and how do we know who might be the aggressor?” Or they would ask these questions that were uneducated and uninformed. And so that leaves the survivor afraid. Who’s here to protect me if I’m asking for help? But when help comes, help continues to create barriers by being homophobic, by being heteronormative in their thinking about what was going on. There was language like “cat fight” that was thrown out. It must be a “cat fight.”

The system doesn’t know how to [deal with us]. They’re still survivors. It’s still someone who’s being harmed by a loved one. So it clicked a lot for me in those kinds of exchanges that places like AVP and advocates in the LGBTQ community needed to be at the table when it came to intimate partner violence, and in particular, dealing with a legal system that was and is pretty homophobic in its thinking and ideas about defining relationships, and then how you deal with relationships where there is abuse. And it was so rampant, the homophobia that existed. I’m not in the system now, but I pretty much know that not much has changed. But it was moments like that, I think that definitely left an impression on me in terms of, I knew this agency was going to step in and be able to bring the information, the sensitivity, the language to support survivors, and also educate those who were impacting the lives of survivors.

How has AVP’s work impacted you personally?

I want my social work students when they graduate to not go out and harm people. I want them to go out and really be very aware and mindful that what they say and what they do can harm, even if we don’t know that we’re committing a microaggression. I just had a meeting the other day with a group in the lab, and a whole conversation came up around misgendering. And to sit in a class, and again to have the experience of being misgendered is unacceptable anywhere, but here where we are at a social work school.

What are some of your crucial learnings from your time at AVP?

Be ready to work. Every meeting they’re consistent on being ready to work, ready to roll sleeves up, ready to have the hard, hard conversations about what direction we really think we need to go. I’ve just been impressed by that.