Mohamed Amin originally came to AVP as a client in 2013 and quickly became an organizer to raise awareness about hate crimes and create community for queer Caribbean voices in NYC. Mohamed launched his own nonprofit, the Caribbean Equality Project (CEP), in 2015 and has continued to uplift, connect, and serve others all while telling his story. After Pulse, Mohamed advocated for queer Muslim voices and organized conferences, historical retrospectives, and exhibitions. His community work continues to inspire.

AVP spoke with Mohamed about the process of coming to AVP as a client, centering immigrant communities, and cultural competency.

How did you first come into contact with AVP?

That’s a really important question in my journey to AVP. In 2013, my brother, partner, and I survived a hate crime incident in Richmond Hill, Queens, in our neighborhood of Little Diana where I currently reside. Through that incident, we were left traumatized and harassed by the police and didn’t get any support to prosecute the hate crime incident as a hate crime. It took a toll on our mental health. It took a toll on our relationship with our community, our sense of safety, and what it means to be openly queer, Indo-Caribbean, Muslim immigrants in New York City.

I found out about AVP through a colleague of mine, and he recommended that I contact them for emotional support, legal support and training with the media, and assistance with navigating the NYPD. We organized a rally in Richmond Hill, Queens to raise awareness of anti-LGBTQ violence, hate crimes, and hate speech in our community. AVP was one of the co-sponsors of that rally.

When I reached out to AVP, they scheduled me for an intake. Through that process, AVP provided my family and myself with counseling services, support with navigating the NYPD. And, also media training, which helped immensely because we had no experience in working with the media and how our narratives were going to be changed or even used against us because we were hesitant to even speak to the media about the incident. But also, we were fearful because we know that Richmond Hill is a very Caribbean community; it has immense ties to the local NYPD, and we didn’t want to experience any type of backlash from our advocacy and our visibility.

Through being connected with AVP, I learned about their Speakers Bureau program. The program itself was geared towards building community leaders and being empowered to tell your stories. I signed up and I was selected to be a part of that program. Eventually, I graduated.

One of the manifestations of my experience at the Speakers Bureau program was to create an organization that provided programs and services for Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants in New York City, and the Caribbean Equality Project was born out of the Speakers Bureau program.

Shortly after I graduated, I started meeting with community members. I started hosting focus groups in our community to get a sense of what could be done. I quickly realized that people didn’t know where to go for support. Other community members had similar experiences to ours, but they were unreported because they were not out to their families. They feared backlash, they feared their sense of safety, and they also feared being abandoned by their family for being who they were. Even though they had experienced hate violence and were traumatized by it, they kept it to themselves to protect their housing and their stability.

In 2015, I launched the Caribbean Equality Project the same day national marriage equality was announced, June 26th, 2015. So we share this incredible anniversary in our nation’s history. From then to now, the Caribbean Equality Project has become an incredible organization in New York City that advocates for and represents Black and brown Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants in New York City.

When you came to AVP, what made you feel they were the right fit to go through such an intense process with?

For me, as an organizer, a lot of the work that I’d been doing was very local, very immigrant-focused, and done in a culturally responsive way to reach Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants in New York City. I didn’t have the knowledge and the skillset to continue growing as an organizer. The Speakers Bureau program allowed me to develop those skills. I always credit Lala Zendale and Chanel Lopez, two incredible Black and brown trans women, for taking me under their wings and for believing in me, and for guiding me through the Speakers Bureau program. Years later, these incredible women have become my supporters. I see their growth as leaders in our community, and I am a reflection of their teachings. AVP facilitated this opportunity for a queer, Indo-Caribbean Muslim organizer in New York City to have a voice, and to be visible, and to be empowered.

What have you taken from your time with AVP into your own organizing work?

I think the one thing I have adopted and made very present within the Caribbean Equality Project is the need for culturally competent mental health services. Within New York City, we don’t have access to culturally competent, culturally proficient mental health counselors. Oftentimes, Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants are forced to sit with a mental health professional and retell their stories and have to educate counselors on their cultural identities and their ancestral history in order for that mental health professional to have a better understanding of who they are. That process is often retraumatizing. That process often looks like re-victimization. As a result, our community members don’t continue to get the care they need.

I’ve adapted this model to center cultural competency in mental health care, in our work. That is the one thing I have taken from AVP but also have been educating AVP on how their work can also be more culturally congruent. That has been done through cross-cultural workshops. It’s been monthly meetings with AVP staff on how to address and respond to Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants who are experiencing mental health crises, who are experiencing abandonment, who are experiencing isolation. As much as I’ve gained and learned from AVP, we have also been training and educating AVP on how to better support Caribbean LGBTQ immigrants in New York City.

Why do you think organizations like AVP are necessary?

The existence of AVP provides a space for community members to receive services that are often unobtainable, services such as mental health care, access to resources to address intimate partner violence, safety planning, and tools on how to report violence.

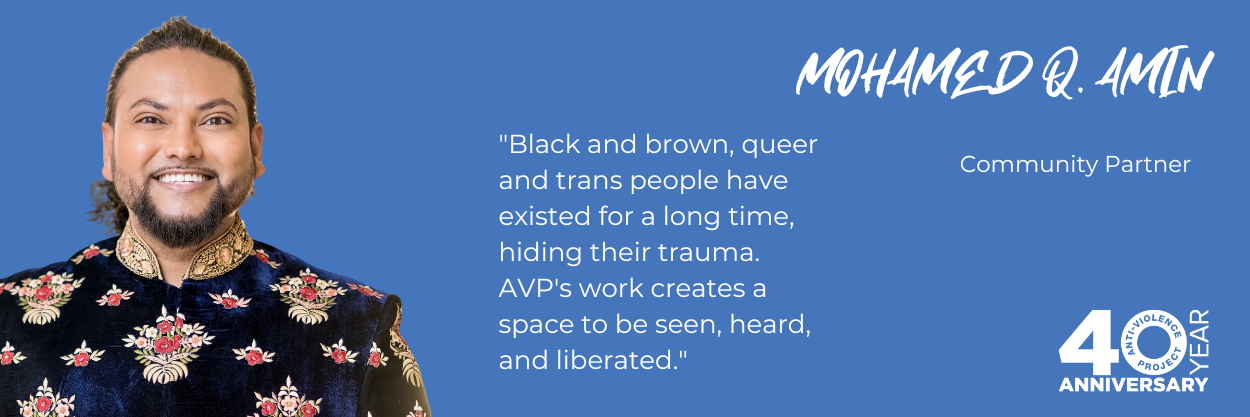

Black and brown queer and trans people have existed for a long time, hiding their trauma. AVP’s work creates a space to be seen, heard, and liberated. As an organization that has stability, I also view AVP’s existence as a vehicle to support grassroots organizations that are on the ground serving LGBTQ immigrants. AVP’s role in that work looks like capacity-building trainings, community education partnerships, and financial redistribution.

There’s an inequity that exists within our LGBTQ movement that prevents immigrant-led LGBTQ organizations from thriving and AVP’s role in this moment of our history is to correct the harm that have been done by larger nonprofits.

I think AVP’s work is critical, and I think their support for grassroots organizations is also critical. I often think about the equity that could exist if larger nonprofits supported grassroots organizations, and that could look many different ways. It looks like amplifying our work on social media. Or, sharing a fundraiser that a grassroots organization is organizing to their listserv. Or, a campaign that they have organized. Or, simply recognizing on-the-ground community members at an award ceremony to highlight their work. As an organizer, that’s what I’ve done. I prioritize and center the marginalized and impacted community members that are often unseen and unheard. I think larger nonprofits could do that without tokenizing or exploiting the labor of LGBTQ immigrants. I think in a lot of ways, my work with the Caribbean Equality Project is also a form of accountability, and when we work with partners, we are asking for equity in that partnership.