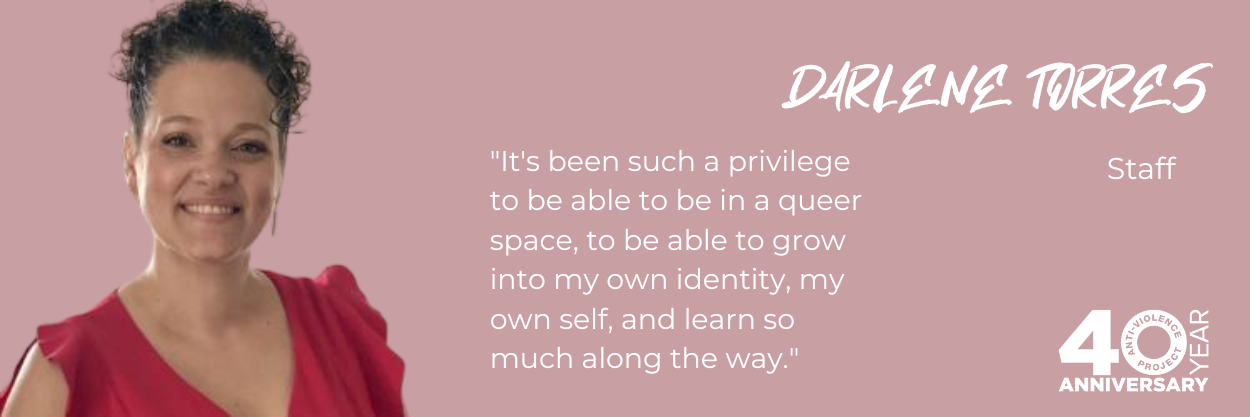

Our current Director of Client Services, Darlene Torres, has been with AVP for almost two decades. Darlene has demonstrated a powerful ability to create a welcoming community for all.

AVP recently caught up with Darlene and discussed sustainability, the hotline, and spiritual violence.

How did you first learn about AVP and how did you first get connected?

I learned about AVP back in 1999. I was working at a reproductive health organization and AVP’s hotline training flier came across my desk. My best friend who worked with me saw the flier and said, “We need to take this training.” And I said, “I’m not going to take this training because I’m trying to figure out my own stuff. How am I going to help someone else in crisis?”

So, of course I took the training and I was a hotline volunteer for four and a half years. The hotline training was life-changing, just meeting community, understanding how violence impacts LGBTQ communities, understanding more about myself and my identity and the hate violence that I was experiencing, that I didn’t have a name for, from family members.

I was hired back in 2004 to work in our Community Organizing and Public Advocacy department. I moved up in that department and started managing the hotline program and the training institute. So I was now managing that program, the hotline, that was so instrumental in my life. I did that for about eight years before moving into our Client Services department and it’s going to be 10 years now that I’ve been in Client Services. I’ve been with AVP now 18 years.

How have you committed to this work for almost two decades? That’s a really special thing.

It’s been such a privilege to be able to be in a queer space, to be able to grow into my own identity, my own self, and learn so much along the way. At AVP, we’re not perfect. We’re all aspiring allies in one way, shape, form, or another. For me, doing the organizing work that I did for so many years, really looking at things on a macro level, shifting policies and being a part of that team, a part of that think tank, if you will, and just being connected to community, it’s just always so rewarding. And then when I went back to school and got my Master’s in Social Work, I decided to apply for a position in our Client Services department because I wanted to be able to take the macro into the micro. I wanted to work directly with clients to be a part of that journey with them.

So it hasn’t been easy all along the way because doing identity-based work is difficult, but It’s just been so incredible to be able to be in spaces where I’m learning, where I am amplifying the voices of survivors and of community [members] that may not have that space, that room, that safety, and doing it carefully, or trying to at least. I can’t think of any other space to be in right now.

Are there any key moments or things that you’ve witnessed throughout the years that really stick out?

I’ve been with AVP so long and I think I’ve had five Executive Directors at AVP since I’ve been here. I think every leadership brings different priorities and I think that it has been interesting to see how we have grown. When I started at AVP, we were very small and now we’re quite large. Our Client Services department is the largest department in the organization. We have our economic empowerment program, understanding that violence takes a financial toll on folks. And I feel excited that we started that program six or seven years ago. Adding our legal department to our organization and to our wraparound services has been super instrumental in really getting survivors what they need.

How has AVP impacted you personally and vibrated into your own life?

Starting as a hotline volunteer, [AVP helped me] really understand the family violence that I was experiencing at that point in my life. Being able to name it felt really empowering. It was a painful process, but it felt empowering to be able to have the language and have the space to actually talk about it and think about it.

AVP has really offered me a lot of opportunities. We use movement language like oppression, systemic racism, structural violence, state-sanctioned violence. And that was language that 20 years ago, I didn’t have. And so to be able to be in spaces to have those difficult conversations, to be the listener, to really be able to connect the dots, to me was just life-changing and continues to be life-changing.

There are not a lot of organizations like AVP, that are willing to sit in the discomfort of difficult conversations on oppression as it looks internally at the organization, not just what we say externally. We had to look at ourselves and make sure we are living our own values, which can really be a struggle. And so we’ve been able to do that and it’s not been easy, because that work should never be easy, but we have the space to actually have those conversations and incorporate the voices of survivors–internal and external to the organization. That’s been life-changing and incredible and really a gift.

A year ago you were on a panel about Spiritual Violence, can you talk to me about that experience?

That panel was so powerful and so needed. The hate violence that I talked about earlier on [with my family] was spiritual violence. I think all too often, people who think about queer lives, queer identities assume that folks cannot be spiritual or don’t understand spirituality. And for me, in my journey,… I finally understood how I was able to separate being a religious person and what it meant to be a spiritual person. And I think for the panel I wanted that really to come across, that queer people are spiritual people, can be spiritual people, and should be if they want to, and that there’s room for that.

So much of the homophobia, so much of the transphobia and biphobia exists because of the religious undertones that feed into all of the conversations. And that’s what happened to me. It was like my family reading the Bible to me, telling me to turn to this scripture and having their own interpretation, but not making room for my own interpretation. [People who use religious] rhetoric have [a lot of power over] queer lives and how we think about ourselves and how we feel. [We might think], “that’s not for me anymore. That’s for other people that are not like me.” But that’s just bull!

Spirituality can look like whatever you want it to look like. It could just be looking at the sun, looking at the leaves that are on the floor, just thanking the universe for another day. It doesn’t have to be in a church or a temple or synagogue or a mosque or anything like that, it’s how you embody spirituality and you get to make that look whatever, however, you want it to look. I just feel like it was a pretty incredible experience. Especially having faith leaders be a part of that conversation and naming all of the messed up ways that other faith leaders use [religion] against queer lives. I felt so moved and honored to just be a part of the conversation.

And there have been moments in my work with clients where I may say that safety [can include] emotional safety, physical safety, spiritual safety, and their eyes just light up, like, “We can talk about that?” And it’s such a door opener for folks to feel like, “Ooh, I can talk about spirituality with you. I don’t have to ignore that. I don’t have to be afraid of it.” And that to me is just a gift. It’s just like, Wow. Yes, let’s talk about it.