This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.

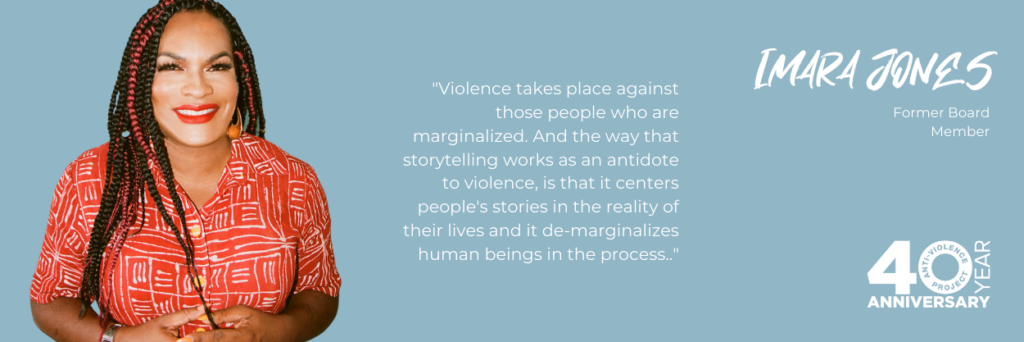

Imara Jones’ work as an AVP board member and journalist are steeped in the power of narrative to confront violence. From her work as a documentarian to her work as a podcaster, Imara has leveraged the ability of stories to create empathy and change. “I think because violence is one of the biggest challenges that our community faces, and violence in all its forms, I think that the work is so critical. I know that was a driver for me. It’s the focus on violence, and the pressing need to address violence in all its forms for our community.”

Connecting the way violence and dehumanization coincide, Imara discussed the way policy and story go hand in hand. Imara initially started at AVP on the Communications Committee before becoming a board member. Here she details her anti-violence work, her initial involvement with AVP, preparing for the 40th Anniversary, and more.

How did you first learn about AVP?

I think I first heard of AVP because members of my community, specifically my friends, worked there. By going to their parties and gatherings, and even some AVP events, I learned more about its work.

I think at some point after Trump got elected, I actually came up with the idea for my first TransLash documentary. Because I knew people at AVP, I had an interview with Bev [Tillery] to talk about anti-trans violence, in fact violence in all of its forms, as part of the backlash embodied by Trump. After that, Bev spoke with me about the possibility of greater involvement at AVP. Part of that involvement was joining the Communications Committee, which you didn’t have to be a board member to be on. Serving on that committee then led to me being asked to become a board member. It was these ever-increasing ways of involvement and knowledge about the organization which all then built on each other.

What were your early days working with AVP like?

They were busy. It was a time when a lot was happening at the organization, in terms of trying to respond to the uptick in violence that we were seeing in the era of Trump. Needless to say, because it was the greatest wave of anti-LGBTQ violence in years, there was a lot to do. That then led into work for the 40th Anniversary of AVP, and then the response to COVID-19. Coronavirus of course led to so many challenges which required our attention and brainpower. Despite the stresses, it has been an exciting time with important work.

How do you keep your momentum with the work you do?

One, it’s the way that I generally approach commitments. Once I’m committed to something, I’m committed to something. I also think that the work, as I said, was really important. I had personal connections with people that I knew, who had worked there. Thirdly, the work of my colleagues was really important. Seeing how hard the staff there was working, across the board, is also a motivating factor. All those things together.

AVP’s a part of some really important visible work, such as the support for Layleen Polanco, and the work around ending solitary confinement. That dreadfully painful episode for our community was a very important time. The needs of our community are fuel for me. They help to keep me going.

What are some favorite or important memories you have of your time at AVP so far?

The 2019 Courage Awards, that was a fun time, and a fun memory. Another was a panel that I moderated, for the 40th anniversary at Square Space, where we spoke to people who helped found AVP, those who work there now, and others looking ahead. It was really a past, present, and future examination of AVP which was incredibly grounding.

I guess those times when our community can come together stand out for me. This includes the Layleen Polanco rally in downtown, not long after she was murdered. Despite the assaults on us, I am always lifted up by how we respond and raise each other up. Even though that was a searing and painful time and remembrance, it underscored the power and beauty of our community. That’s who we are.

How have you taken your work with AVP into other spaces?

I think that centering the need to combat violence in all its forms is something that I think about in every way. I think of violence as being a very layered phenomenon. Because it is such, I continue to understand the important work that narrative plays in combating violence, in addressing cultural and social violence in particular. I think that I always keep that front center in everything that I do. I think in some fundamental way, a key part of everything that I do is anti-violence work.

What role do you feel that narrative plays in combating anti-violence?

I think that narrative is important in a lot of different ways. One, I think violence takes place against the reality of dehumanization. The more that you can center the humanity of people, and expand the consciousness of other people about the humanity of others, is the degree to which you can combat violence. Violence takes place against those people who are marginalized. And the way that storytelling works as an antidote to violence, is that it centers people’s stories in the reality of their lives and it de-marginalizes human beings in the process. Thirdly, narrative is important for people who make decisions about anti-violence work from a policy level, because a lot of times they don’t think about, or have awareness about the way that violence impacts a range of communities, especially LGBTQ communities.

So narrative plays lots of different roles in anti-violence work, and it’s not immediate.

The thing that is really important to understand about narrative is that it’s a longer term project, of working for anti-violence. When an event happens, people don’t need a story told to them. They need help and support. I even think that we see that in Layleen’s case. The ability for her and her family to be able to tell their story, and for people to understand the impact on them. To understand what it was like for them to lose their daughter and their sister. To tell the story of what solitary is like, that’s been a large part in them getting more justice, and an essential part of them getting laws advanced. But that takes time.

The laws are not yet where we want them to be, but they won’t change with story, without new narratives. That’s why I think that story is really important. It helps people understand the consequences and the important remedies of violence.