This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.

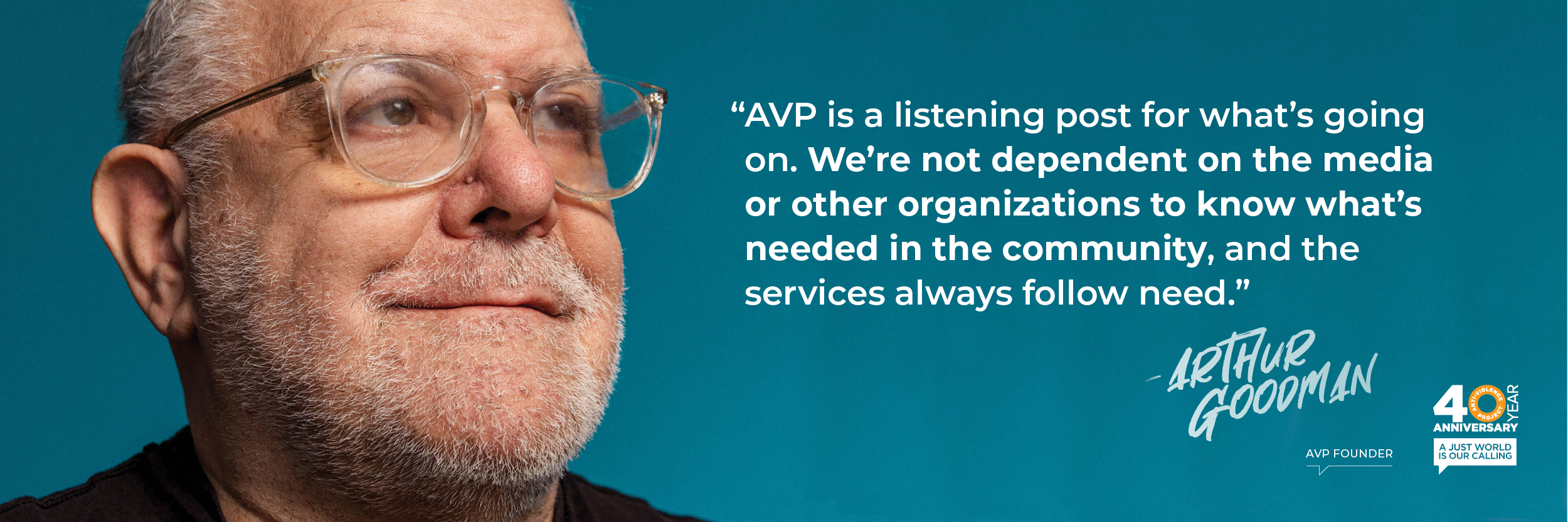

A former member of the first neighborhood-based gay and lesbian group in New York City, the Chelsea Gay Association, Arthur Goodman was one of AVP’s founders in 1979. He holds a Masters of Public Administration from CUNY Baruch College, and currently provides financial planning services, specializing in the LGBT community and unmarried opposite sex couples through Good Man Financial Planning.

Arthur shares how AVP sprang out of a mutual need communicated by survivors of violence at the Chelsea Gay Association, obstacles AVP faced as they worked to serve the LGBTQ community in New York City, and his hopes for AVP in the future.

What was your role in the creation of AVP?

Well, I think to understand, at least my part of it, you have to understand about the Chelsea Gay Association, which AVP sprang from. As I think about it, it was a Petri dish of an organization. I had started it coming from the Gay Activist Alliance, which ran by parliamentary procedure. So I was interested in a much looser organization and we actually discovered that we didn’t need much of a structure. We had one steering committee which was made up of whoever wanted to show up for a steering committee meeting — anyone could come and vote. Essentially anybody who had a concern or an interest in doing anything could go ahead and do it, use the Chelsea Gay Association name. We weren’t spending very much money. We had enough money for whatever we wanted. So people could start things.

People were being beaten up on the West side of Chelsea when they were going back and forth to the bars. And that was a concern. So a couple of people, essentially, Jay Watkins and Russell Neuter, took the initiative to start dealing with it. They and some other people did basically whatever they felt was best to do and we raised whatever money they needed. And so it came out of this very free-form, unstructured environment.

But what came about was that people needed services. They needed to be connected with the police to report incidents. They needed to get in touch with victim services to receive compensation and help with bills from medical issues and stuff like that. It became apparent that the Anti-Violence Project needed structure. I think my claim to fame came when we had a steering committee meeting and I suggested that the Anti-Violence Project spin-off and become its own organization.

What’s something about AVP’s founding that most people don’t know?

That we didn’t know what we were doing. We were making it up as we went along. But the mere fact that people were gathering the information in one place about the incidents and what happened, they became the experts. The Anti-Violence Project became the expert on anti-gay violence, pretty much for the nation.

The other thing that came up a couple of years later when I was on the board was we believed, as most people believed, that domestic violence was about men abusing women. And it was really a shock to discover that we were getting calls about domestic violence among same-sex couples.

Did you foresee AVP becoming what it is today? Is there something you’d like to see AVP accomplish in the next 40 years?

Not in the least.

I was incredibly impressed that we had four staff in the mid-eighties and met payroll. I am not surprised or shocked that there’s a need for such an organization 40 years later. My long-term vision, in terms of the gay community, is remarkably bad. I thought that gay marriage was a crazy idea when there were one or two people talking about it. There were people in Chelsea Gay Association who were working on tracking how people were being depicted in media and I thought that was irrelevant. What was important to me was having demonstrations and going for civil rights. I see now how incredibly important and effective GLADD’s work has been. So I have vision in some things and really bad blind spots in others.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about AVP and your involvement?

I think one of the things that’s important about AVP is that it’s a listening post for what’s going on and the fact that the number is out there and people call, allows us to find out what’s happening. We’re not dependent on the media or other organizations to know what’s needed in the community, and that the services follow need rather than us deciding on theory what the need should be and what the program should be.

There’s that Margaret Mead quote about how a group of like-minded people can make enormous change and in fact, that’s the only thing that ever has. At Chelsea Gay Association, we were a bunch of people just seeing what would happen if you put a whole bunch of gay people together. It was a very social and fun gathering, but we dealt with what came up and we weren’t afraid to be ignorant and do our best.

I understand that, at this point, it’s important to professionalize nonprofit organizations and have them run smoothly and have protocols and all that but to really encourage people that as things change, grassroots activity is incredibly important and can lead to all kinds of things. And bake sales are important, that level of activity is important.