This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.

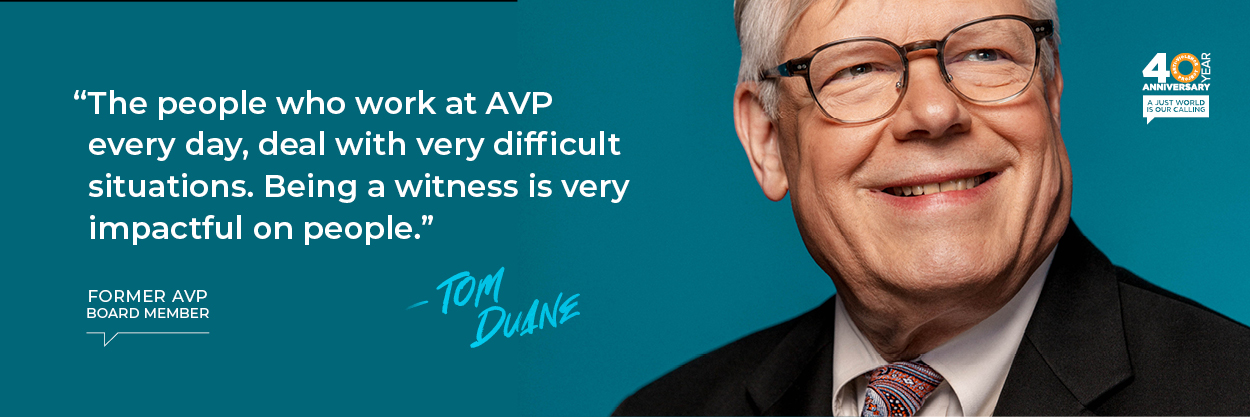

Tom Duane was the first openly gay and openly HIV+ member of the New York Senate and has been integral to legislative reform in the state to better protect LGBTQ+ and HIV-affected people.

A former AVP board member and hate violence survivor, Tom’s legacy includes sponsorship of same-sex marriage legislation and the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (GENDA) in New York State, as well as the passage of the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act.

Here, Tom shares how his participation in Chelsea’s Gay Association led to the founding of the NYC Anti-Violence Project, justice reform, and the importance of mental health support for service providers and clinicians.

How did you first get involved with The Anti-Violence Project (AVP)?

Even before there was an AVP, there was a spark that I think ignited things that created the space for AVP to be developed. I was a member of something called the Chelsea Gay Association, which was the first neighborhood-based gay organization. At the time it seemed almost radical. It was 1977. There were a lot of gay male bars along the waterfront in the teens and the twenties along the West Side Highway. There was a New York City Housing Authority development in Chelsea called Fulton Houses. And the young people there, men, were beating up gay men as they walked towards the bars.

I created a forum where we invited the president of the Fulton Houses Tenant Association to come, Helen Gilson. She came to the forum and she heard some of the stories of what had happened, and towards the end of the forum she stood up, she was obviously touched by this, moved by it. She said, “Well, you’re not my cup of tea, but I don’t think you should be beaten up.” Which was a huge victory in so many ways. Then, she put out the word, “Stop it.” The violence stopped.

As a result of that, there were some people in the Chelsea Gay Association who started sort of an anti-crime thing that was both gay and non-gay in Chelsea. It was really out of that that the Anti-Violence Project was born. It was really very much needed. I knew of people who had been the victims of violent attacks, and I even knew gay men who had been sexually assaulted. The need absolutely was there.

So from the very beginning, I supported AVP. It was probably in many ways, for me, the most important LGBTQ organization.

In 1983, I went to visit my parents, and I was in the parking lot of a gay bar, and a car pulled up and two guys jumped out and called me anti-gay slurs, and I knew it was like, “Ugh, I’m in trouble here.” Sure enough, they started to kick me and punch me. I just protected my head and started to yell for help. Finally, someone came out of the bar, and they scattered. Fortunately, nothing was broken, but I was really bruised up and in pain. I reported it to the police, and maybe two weeks later I called to ask about my case and they told me, “Oh, it’s over. They pled out to a misdemeanor.” I didn’t get to confront them. It wasn’t even that they pled to a misdemeanor. That would have been okay with me. I would’ve liked them to say that they knew what they’d done was wrong, but really what I objected to is that it didn’t count.

That was not the only time. That was just the worst time. The AIDS crisis hit, and that was another reason that people felt entitled to beat up gay people. I had someone throw a full bottle of beer at me, just missing my head. I had another time, a guy just smashed my face. I was wearing my glasses, broke my glasses, cut under my eye. That doesn’t even cover the verbal harassment–you don’t know when someone is yelling some anti-gay epithet at you whether it’s going to turn into violence or not. That needs to be reported–that it’s happening and where it’s happening, and where resources should go to make safer places for people.

The thing about violence against gay people is that there was no one collecting any data on it. I became very vocal that we needed to pass what was to become hate crimes legislation, but especially to document what happens to queer people, Latinx people, people of color, Jewish people, women when there’s a bias-related crime. We need to have data because you can’t fight something if you don’t have the data to really go at it.

Eventually, I ran for office, I ran for the city council, and I did whatever I could there. Then, in 1998, the State Senate seat that included my council district became available, and I ran for it. People said, “Oh, why would you ever want to be a minority Senator? You can’t get anything done.” I thought to myself, “If you think you can’t get anything done, you won’t get anything done. I’m going to get stuff done.” In my first term, I made a speech on the floor. Telling my story on the floor of the Senate, it changed minds. There was a Republican Senator from Staten Island who said, “We have to do something about this.” The next year, the Senate passed hate crimes legislation.

How did you come to be a part of AVP’s Board?

I went to one of the AVP events and Sharon Stapel, who was the Executive Director, was kind of standing by the elevator when I got off and we talked for a minute, and then she said, “Would you join our board?” I was like, “I’m going to join one LGBTQ organization and I’m going to do one non-gay organization.”, I said “Yes” to Sharon. I was very thrilled to be on board.

What do you want to see AVP accomplish in the next 40 years?

I want it to go out of business. I want there to not be a need. A boy can dream. I would like it to be funded in a way that whoever is the Executive Director, whoever the board members are, they don’t always have to be worried if there’s going to be enough money to keep providing the services. They raise money and they spend it all, and then the next year they may not have as much and that’s rough. Everyone takes pay cuts. You know what I mean? I would like it to be that there’s enough money that comes in all the time. Because again, the people who work at AVP to a person are just wonderful people.

Also, the people who work at AVP every day, day in and day out, they deal with very, very difficult situations, and many of them don’t work out very well. I’d like to be able to permanently have some place for them to go to right there. Being a witness is very, very negatively impactful on people. I would like to be able to institutionally make sure that the staff are taken care of emotionally and in any other way that they need help. I want to make sure that there’s cash flow for them to do what needs to be done.