This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity. Some of the content may be triggering for survivors.

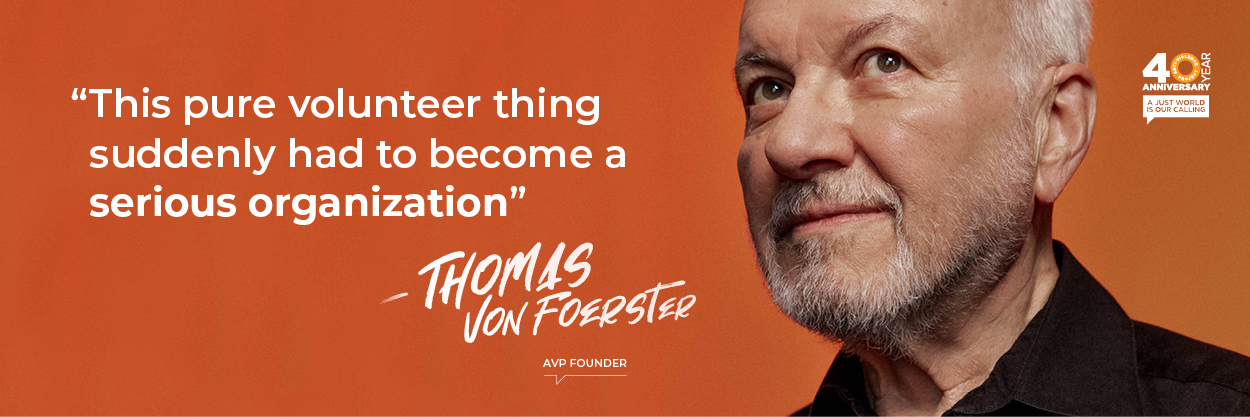

In 1978, Thomas von Foerster moved to New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood as a 37-year-old gay man in search of others like him. He soon found community in the Chelsea Gay Assocation (CGA), a social group for gay men. His involvement in the association quickly grew, and he became treasurer as well as the editor of the monthly newsletter with over 1000 members.

When queer men began to face violent attacks coming to and from the gay bars on the westside of Manhattan, some in the CGA rallied to support the survivors. As the editor of the newsletter and keeper of the checkbook, Thomas found himself by happenstance in a unique position to promote the beginnings of what would become the Anti-Violence Project (AVP).

What led to the formation of AVP and how were you involved?

Back in the early eighties, there was a community group called the Chelsea Gay Assocation started by Arthur Goodman and a couple of his friends. When I moved to New York in ‘78, they were just getting started and I joined up because I lived in Chelsea at the time. In the earlier eighties, the gay bars by the water front, The Eagle, The Spike, The Cock — serious leather bars were down there. To get there from the rest of the city you had to walk past the big housing projects that were along the river there. There were several really nasty attacks. When a couple of people in the CGA went to talk to the cops about these attacks, the cops claimed they had never heard about them. The CGA started helping people go to the cops, file complaints, and then follow up to make sure the complaints weren’t just filed away in the wastebasket. They asked if they could use the answering service from the CGA as a hotline for people who were attacked.

The two people who were active in starting AVP were Jay Watkins and Russel Nutter. They took it very seriously and really organized to make sure that people that got attacked knew that there was this hotline, and they started asking for help, for instance, organizing self defense classes in some of the bars there.

That was the sort of thing that led to starting the hotline. Then in the course of things, the hotline became quite important. We started handing out flyers at the bars and everything else. Assemblyman Richard Gottfried heard about AVP and realized this would be a good thing to support to improve his relations with the gay community in Chelsea. He proposed donating some state funds to the organization to help it get started. So this pure volunteer thing suddenly had to become a serious organization.

What were the differences between CGA and the newly formed AVP? What was the impact on the community?

CGA was a purely social group whereas AVP was always an advocacy group. There were lots of people in the CGA who really resented AVP taking over the focus and requesting money from us all the time because they thought we should use it for more games and things. The CGA was a very different kind of group. Lots of people met dates and friends through the CGA.

There were the same sort of divisions there are today. There were the Republican gays who just wanted to blend in and thought everything would be perfect if everybody was just like them and didn’t make waves anymore, and tried to make sure that nobody noticed that they were living with another man. And then there were the flamboyant queens who just can’t hide it who are the ones that actually get attacked. There has always been a tension between those opposite ends, and of course lots of people in between. All of the sort of safe people were saying ‘well if they just didn’t dress that way, or walk that way, nobody would attack them so why are they doing that!’ It’s still there.

Were you aware of other anti-violence movement work happening at the time?

I learned several years after the New York AVP started that a couple of similar groups existed elsewhere, for instance in San Francisco. I met and briefly dated a guy from San Francisco who had been involved with the efforts there, I made sure that people knew about the connection. By that point the New York AVP was already aware of other groups. They sort of took a leadership role in connecting everybody together.

What is something about AVP’s founding that most people don’t know?

The attack that actually precipitated, that was really serious, that Jay and Russell became involved with, was the Episcopalian minister in charge of the Holy Apostles Church. He was heading to The Eagle or something and got really seriously beaten. Jay and Russell were friends of his. When the cops did not record the beating, they got really upset and that’s what really prompted them to make sure that these things get recorded.

What are some ways you’ve seen AVP transform and evolve over the last forty years?

There were always people with slightly different focuses. For instance, very early on Jay and Russel met a guy that had been going to the courts when the gay bashing cases were being heard and trying to by his presence just simply point out that the gay panic defense was not really valid. Even though lots of people at that point were getting off for beating or even killing people.

So they helped recruit more people for his court watching project. That was an early project and I don’t think that exists anymore but that was sort of one of the sidelines to the Anti-Violence idea that was very useful for a time.

I think for the defendants and everybody, it’s very useful to have support in the courtroom.

What would you like to see AVP accomplish in the next forty years?

I’d like to see AVP become unnecessary. That means that people stop directing violence against minorities of any kind including queer and trans people and all the people that are constantly being attacked, which the current administration in Washington is encouraging. It would be nice if we didn’t have to fight that sort of thing. I think that’s going to be an effort of a lot more than forty years but I think everything one can do to make AVP unnecessary would be great.