This interview has been shortened and condensed for clarity.

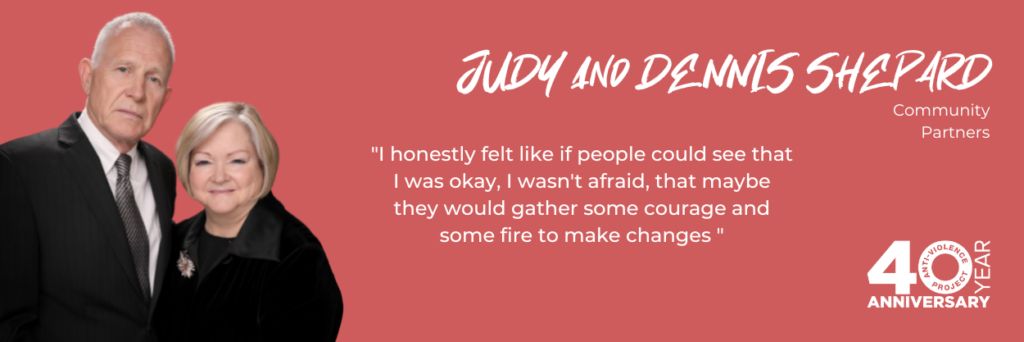

Judy and Dennis Shepard have dedicated their lives to the work of ending hatred-based violence, by turning their own grief into action. The work to end violence is a long road. The Shepards joked about continuing to put off retirement due to the continued need for vigilance. After losing their son, Matthew Shepard, to anti-gay hate violence, the Shepards found numerous organizations like AVP were ready to step in and commit themselves to the work that needed to be done.

Judy Shepard was the recipient of a Courage Award in 2003 for her work. In 2009, she authored a memoir about her experience titled The Meaning of Matthew. The Shepards have continued to speak to legislators, corporations, at colleges, and in many news outlets. Here the Shepards talked to us about their vision of anti-violence, community, Matthew’s legacy, and their work with AVP.

How did you first come into contact with AVP?

Judy Shepard:

When Matt was killed, we heard from everybody about everybody else. Everybody already talked about the work of Anti-Violence Project. We asked a lot of questions about how are people in the community handling this situation because we know it’s not new and what can we do to help. That’s pretty much how we found out about everybody.

When Matt was still in the hospital, we began to get a ton of cards and letters. Many of them contained money, like go buy lunch or a cup of coffee, or we’d like to help pay for hospital bills or whatever. When Matt passed, we had all these communications asking us to do something to take advantage of the moment or empathizing with us or sympathizing with us and sharing their own stories.

Also, we had this money and we didn’t want to use it to pay for medical bills, so we had this idea that we would start this 501(c)(3) to honor Matt and his community. We had really no idea what we were going to do with it. We had a family friend who was an attorney who got it all set up for us. We actually incorporated on Matt’s birthday, December 1, 1998, just with the idea we were going to help young people Matt’s age, his peers, have a better life in their own future. We weren’t really sure how we were even going to go about it, but we wanted to do something.

We also didn’t think it would last more than a couple of years, if people would remember Matt’s story. People move on from one tragedy to the next, so nobody is more surprised than us that we’re still doing the work.

Dennis Shepard:

Or disappointed.

Judy Shepard:

Or disappointed, but we’re still needing to do the work. That was, basically, the genesis. Then the following year, ’99 … We kept a low profile because the trials were going on, so we didn’t really kick into foundation work until 2000.

Dennis Shepard:

Judy spent most of her time traveling and speaking to colleges, universities, and organizations just to get the word out because she figured, again, she had a little bit of time, very little time, and [she wanted to] take advantage of it. Her first speaking engagement was the U.S. Senate. For her, being the introvert that she is, and me being in Saudi Arabia, I keep thinking about that, what a shocker that must’ve been for her to have to speak to people, let alone have to speak to people at such a high level.

Judy Shepard:

Yeah, it was. I started doing colleges and I signed up with a speaker’s bureau. A friend of a relative thought I should do it, so I thought I’d give it a try, which was weird for me, as Dennis said, as an introvert, to do that. I honestly felt like if people could see that I was okay, I wasn’t afraid, that maybe they would gather some courage and some fire to make changes because I know everybody was deeply affected by what happened to Matt, that what happened to him could have easily been them. It was exhausting for an introvert to be doing that, but I really needed it. I needed it to survive, I think.

Dennis Shepard:

Also, the fact that she was talking about it to show to other parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts, whoever it might be, the adults in the room, that she loved Matt for being Matt. Anything else was secondary.

What was it like to speak before the Senate?

Judy Shepard:

Well, I had some really good people with me. The Human Rights Campaign was there with me helping me prepare and create the statement. That’s where I met Joe Biden the first time, Senator Biden. Orrin Hatch was on that committee, I remember.

What I remember the most is how disappointed I was because mostly, I spoke to one senator at a time and their staff. The senators kept leaving [the room], so there were hardly any senators, actually, in the room. There was a panel of us testifying about why we needed [hate crime legislation]. I just remember thinking, “This is really not how I thought my government was supposed to work.” I thought, ”You’re not here to do the right thing. You’re just here. I don’t know why you’re here.” It was very disillusioning for us.

Dennis Shepard:

With them leaving and coming and going, they never felt the full impact of her statement. They might read it. If you read something, as you know, it’s more neutral than it is if you hear the emotions and see the emotions when somebody is testifying.

What went through your mind when you first saw the Laramie Project?

Judy Shepard:

I just knew I wasn’t going to be able to sit through it. I saw pieces of it, but I didn’t see it in its entirety until 2008, maybe. Dennis was much later than that, even. Well, he was out of the country. He has a really interesting story about the first time he saw it in its entirety.

Dennis Shepard:

Yeah. I was able to get from the airport to Washington, DC in 10 minutes because the government was shut down, so there was no traffic. It was supposed to be in a-

Judy Shepard:

Well, originally, it was at Ford’s Theater.

Dennis Shepard:

That’s where it was going to be, right, which is a government-funded venue and because it was shut down, they could not have any activities there because of government funding. They moved it a couple blocks away to a church. As I was walking up to attend, across the street was Westboro Baptist Church. They didn’t know who I was, so I was up there talking to them. We kind of got into it, but then I went in and sat in the back. It was very emotional for me to watch that. They did such an excellent job. Nobody knew I was there until afterwards. Then I went back and met with the cast and crew. They said, “Thank you for doing that. Otherwise, we would not have been able to do the play.”

What role do you think the community plays in combating violence or in anti-violence?

Judy Shepard:

Well, I think it’s huge. They support one another. They tell their stories, which is critical because until they tell their stories, nobody really knows what’s going on—good or bad. That’s just really important, but the support that they give one another and the care that they give one another, even like when they’re out, to watch out for one another and not ever let folks be alone. There’s a protocol to be safe and particularly, in the last few years, it’s been much, much worse for all the marginalized communities. Hate has just been unleashed.

What has it been like working together?

Dennis Shepard:

It’s hell. You can’t get away from her. [Laughing]

Judy Shepard:

I was going to say the same thing. In our whole married life, we’ve never spent so much time together as we have in the last several years because Dennis was working and overseas for a while, well, many years, while I was back here. I did live in Saudi with him until Matt was killed, but then I came back to do this most of the time. It’s been good because we offer a different perspective of a mom and dad and how we regarded the community and Matt’s story and the kind of things that we even talk about now will come from a different place. It’s been really good. I think we support each other and, occasionally, punch each other when we’re talking too much.

Dennis Shepard:

That’s me. That’s me.

Dennis Shepard:

The important thing about all of that, is to see these middle-aged people who were high school students or college students when we lost Matt. They come up to me and say, “I just want to see Judy again and thank her because she saved my life, because I was thinking about suicide and hearing her speak gave me hope. And because of that, I’m where I’m at now. I can’t thank her enough for giving me the inspiration, knowing that someone cared.”